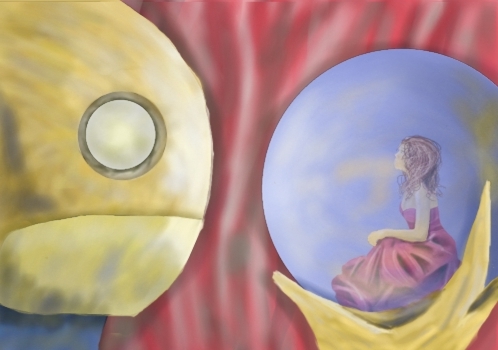

art by Justine McGreevy

Clem

by Cassandra Rose Clarke

When Clem died, I took to eating my lunch in the office with the computer. No one ever went down there except Clem. I couldn't stand the thought of the break room, all the conversation stopping when I appeared in the doorway.

The first day, I pulled a broken-down ergonomic desk chair out of a closet and balanced my soggy tuna sandwich on my knees. I set my Diet Coke on the floor beside me. The computer didn't say anything, just rippled a row of green lights in a pattern that reminded me of the ocean.

The second and third days were the same. I ate my lunch in silence, listening to the fans whirring constantly in the background. The computer's lights rose and fell.

Then on the fourth day, the computer said, "Hello," in a voice like snow falling across an electrical fence. I dropped my sandwich in surprise, tuna smearing across my skirt: after three days, I had begun to assume that the computer wouldn't speak to me at all.

"Hello," I said. The lights stopped blinking.

"Do you know Clem?" the computer asked.

At the sound of her name I stood up. The chair rolled away from me. The sandwich fell to the floor. Even though the room was enormous, with high ceilings and two bright windows, I couldn't breathe.

"Yes," I said. "I know her." I didn't bother to correct myself. I walked towards the door, heels clicking on the tile.

"Are you Alicia?" said the computer. I stopped, turned around. The green lights began to ripple again. "She talks about you often."

The present tense bothered me. It was my mistake to make, not a machine's. "No," I said. "She doesn't. She's gone. Dead. Do you know what that means?"

Clem had explained to me once, as we walked away with greasy paper-wrapped meals from the taco truck, that the computer didn't always understand abstractions about us. But the computer said, "I know. Mr. Allendez told me."

"Then why do you talk about her like she's still here?"

The computer didn't answer. The lights blinked off. For a long time I stood in the middle of the room, in my stained skirt and wobbling heels, but the computer didn't speak again.

I waited a week before going back to the computer. I ate lunch at my desk, and the other secretaries flitted by, putting their hands on my shoulder and asking me how I was holding up. "Fine," I said, over and over again. "I'm fine."

But I was sick of their false sincerity, which was why I decided to see the computer again, because I thought maybe it understood.

When I opened the door to the room all the overhead lights switched on. I leaned against the frame. I felt shy, like the first time I knocked on Clem's office door, when I decided I wanted to meet her.

"Hello, Alicia," the computer said.

"Hey."

"I apologize for my rudeness the other day," said the computer. "I'm not used to the concept of death."

"Neither am I." For a moment I lost my voice. "Especially hers."

The computer didn't respond. I stepped into the room and pulled the chair up close to the computer.

"I've forgotten the way she smells," I said. "I haven't washed my sheets since it happened but they all just smell like me now."