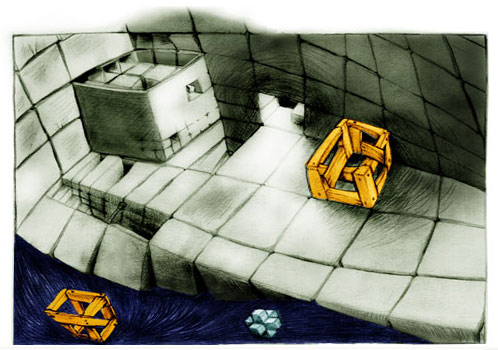

art by Seth Alan Bareiss

Walking Home

by Catherine Krahe

Catherine Krahe lives in Iowa. She plans to save the world by

telling stories and planting trees.

***Editor's Warning: Disturbing, adult tale***

The beekeeper Alsah has battlemagic. When he fights, and he does so only rarely, he breaks necks.

The last neck he broke belonged to a soldier during the war. Alsah reached out, gently, gently, and then it was done. He was alive, the foreigner was not. He cut his hair, his bootlaces, the ties on his shirt and trousers, and walked barefoot to a foreigners' temple to do penance.

There are more necks he would break, if he could put his hands on them.

Alsah lost two sons to the foreigners, child-thieves. His younger son, who laughed and had beescraft to carry on the family trade, died somewhere between home and the occupied provinces. Sharks, or perhaps, mercifully, terribly, serpents, ate his son's body. His older son did his best to keep them both alive, but nothing could be done. That either of them came home is a miracle. It would not be a greater miracle if both had survived, and it is not a lesser miracle that only one did.

Those whose children are lost eventually seek the city, where half-lucky reclaimed children are taken until they can be returned to their families. Alsah walked there alone, and alone he saw the one who survived--he can say the name now, the boy is alive, his name is Bindun--who screamed Papa! and ran towards him, then Alsah swung his miracle son up and around in sheer joy. Bindun was crying, crying because he couldn't keep his little brother safe, and Alsah set him down. Then, still tear-streaked, the boy pulled himself away and stood between his father and two other boys.

"These are my brothers," the boy blurted, and Alsah understood.

Enjoying this story? Don't miss the next one!

"My son's brothers are also my sons. If you like. I don't..." Here he faltered. He had raised two boys from infants to children, and these three had gone beyond child to some realm other than adulthood. "I'm not going to hurt you. I keep bees. I sell honey to the cityfolk. The Queen had some once and she liked it." They stared at him, even Bindun. "Would you like to go home?" he asked his son, his middle son now, the son returned to him from the child-thieves with scars on his arms.

Bindun nodded and took his hand.

Now he walks home with three sons. The smallest has an easy, unwary smile that almost hides how his eyes flick over everything. The oldest looks half-foreign and seems not to care what Alsah does, save that he braces himself to take a fist. They walk together, three shadows made one, and Alsah's apart and impotent.

They don't talk much on the road home. It's two days' walk, less with awkward, silent wagon rides. Alsah wasn't the only one to lose children, nor the only one to recover them, if that word is right. It happens all along the border between their single free realm and the foreigner-held provinces. The neighbors who haven't found their children are most helpful, as if they can conjure their own families out of his impossible luck.

They arrive home to find a bed and several packets of clothes on the porch. "I don't know where you want to sleep," Alsah says, rubbing his hands over his face. "If you want the big room, or the other, or all the same bed. Just let me know and we can get it set up."

Bindun doesn't talk. Alsah doesn't know what he's seeing. The scratches on the doorframe where first Bindun, then his lost brother, stretched up to mark the years? The small barn where Alsah keeps the supplies of beekeeping, the frames, the jars, the expensive broken glass and ant-sticky mess from when he came home and knew, knew, that his sons were dead? The dishes, still laid out for a family of three rather than four or a broken one?

Perhaps the several patchwork pillows his wife made before she died. She'd made one for each red-faced infant in turn, then more, and Alsah had thought she would hate to know they'd outlasted their sons. So he'd crushed the patchwork pillows to his chest and sobbed for all he'd lost, and the next day, he started for the city and traded honey and beeswax for the same false hopes everyone had, and then three boys.

When it gets dark, the boys reach some accord and start shoving furniture around the little room. Alsah waits until it's clear they won't ask, then stands in the door. Bindun and the little brother cringe when they see his shadow.

"Three beds won't fit in here," he says, trying not to hulk, trying to be a beekeeper if he can't be a father. "Take them apart while I work on the big bed, and we'll switch." It doesn't take him long to pile his blankets and sheets in the sitting room or to move his bed. He goes to the boys' room to help, but they work efficiently and he is too much in the way.

It's full dark and dinner's ready when the beds are finally arranged in the big room and the small. Alsah puts a patchwork pillow on each of the narrow boys' beds and ignores the loaf of bread cached under one of the blankets. A bit later, as he lifts the meal from the oven, he feels a sudden, slamming hug at his side. His breath comes out with the force of it. When he turns, ready to serve the pie, Bindun is clattering spoons on the table.

"I think," he begins as they eat quickly, like the guards and warriors he knew during the war, "I think you should see the rest of my place tomorrow. You've hardly gone out. There's the barn, don't go in there without telling me. I have hives through the woods, too. And there's the field and the garden. Stay off the creek path, that's where the mad hermits are, and you'll need an introduction."

Then he looks up and his voice is rough. "If they come again, there are hiding places here and in the barn. From the war." Bindun knows where they are, but he has to be sure for the others. "There's a false wall by the stairs that leads to a second cellar, and a rope to the alarm bell. If they come again, get down there and call for help and I'll run them off."

His sons were taken from the woods, where they were fishing or climbing trees or doing any number of things boys do in the woods. There are probably bolt holes out there, from when everyone drove away the foreign usurpers for the true Queen, but Alsah never saw them. When he joined the road guard, he stayed with the horses.

"Is there anything you want to see?" he asks finally, and the oldest boy nods.

"Does the door have a lock?"

Alsah can't understand the question and his brow lowers. None of the boys flinches, but Bindun and the smaller one sit straighter, as if they have to protect this child who has accused him... or not accused him, only told him what he would have known if he'd let himself.

None of the doors in the house lock.

"I'll see what I can do," he says, and then everyone has eaten.

That night, when he tries the door to their room, just to see, just to know that it's true and he can wake tomorrow with sons instead of with holes in his chest, it doesn't move. He almost pushes it open, but the part of him that destroyed the storeroom, the part of him that knew and hated that his sons would not be simply dead, pulls him back to his own bed.

Somehow, the memorial is the next day.

Alsah had meant to take the boys out, see which hives are thriving, spend a morning walking so they wouldn't have to talk if they didn't want to, the way he grew into a quiet, solid man during the hard years of the war. He had meant to show them the marshy pond where the creek used to bend before the bank collapsed in the fall. He had meant to show them safety.

Instead, he finds himself welcoming the neighbors, who bring food and drink and memories.

"I remember," it begins, casually as always, "his shouting. He was such a noisy boy. I could tell when you were coming because I could hear him getting louder and louder."

"I remember finding him in the woods once, trying to figure out how to move a wild hive. You won't know this, Alsah, he cried and begged me not to tell you. He wasn't more than five, and not a sting on him."

"I remember at the old brewer's memorial, when he was six, he got up on the porch railing and yelled out about how the old woman had chased him away with a broom."

"I remember him bringing me little fish from the creek. Always did that, every time. Not a one of them longer than my hand."

"I remember when he was just born, and he wouldn't stop crying unless his papa or his brother were touching him. I held that screaming baby for an entire night, must have walked halfway to the city around the house, and he didn't stop hardly long enough breathe. But either of you two, you take him and he's calm as anything. And that lasted until he was two!"

As people come and go, sharing memories because they can't say the boy's name any more, Alsah watches them watching Bindun. Bindun doesn't speak, doesn't stand in the kitchen or on the porch and pass on what he knew of his little brother. His face is calm, but there are red scratches up and down his arms. Alsah wishes he could provoke an outburst, something he can comfort.

What kind of memories would Bindun share? Maybe he's right to stay quiet, like the other two. The people here have lost children. Maybe it's right that they not know what it's like on the ships, where rats are bold and a boy can vomit blood until they throw him to the sharks and serpents.

Still, the part of Alsah that breaks jars and closes doors already knows these things. If he couldn't save his son, can he not at least hear of him? Eight years wasn't enough. He wants to know the ninth.

Alsah eventually sees the blacksmith. When he asks for a lock--anything he can do for his boys, anything at all--she nods. "The little one already caught me in the kitchen. He's charming. Showed me the coins to pay for it." Her eyes are kind, more than anything; she was a child during the war and understands that they sometimes have to take care of themselves.

Otherwise, the two new boys, his two new sons, don't play with the neighbor children, and when one of the adults tries to draw them out, they retreat to the bedroom. Alsah walks around the house once and glances in the window; he can see them staring back. The next time, he leaves half a rhubarb pie on the windowsill for them to eat.

Then it's time for him to speak.

"I remember," he says, and for a wonder his voice is steady. "I remember when my two sons left to go check on the hives in the far meadow. They sang while they walked," and oh, he could sing the song now if he thought he had any chance of surviving it, "and my younger son's arms were swinging. They weren't going for any good reason, just to go. Just because. And the last words I called to them were not to get muddy because we'd just done the laundry three days before. And he, and he laughed and I knew he was going to jump in the creek. And then I went back inside."

And that's what he remembers of the last day he had two sons.

The next morning, the blacksmith visits. Her knock is authoritative. The boys grip their knives like weapons until the little one jumps up like a terrier, welcoming her for what she can do.

"It's not a lock, but it'll hold better," she says, holding out a metal bolt. "Which room?"

The three boys watch as she measures the doorframe, pulls out screws, makes the room Alsah shared with his wife into a fortress against any who would enter. "It's solid," she says, "though most of that's the door itself. I think you could break it down if you had to. Fire or something."

Alsah nods. "How much?" The little boy is startled, as if he's erred somehow. Alsah can't speak for a moment, then nods and waves him forward. The child haggles with the blacksmith, aggressively charming, and Alsah stays in the kitchen. When the smith is ready to go, he hands her a sack. "For your trip home," he says, and if she can guess how much he's given her she doesn't mention it. When he comes back into the house after seeing her down the road, he hears the boys talking, a strange child-pidgin.

He leaves again, not wanting them to know he wants to listen.

Alsah, like everyone of his generation, knows that no one comes back from the ships whole, no more than anyone walked through fifteen years of covert rebellion and five of awful, bloody warfare to safe hearts and pure souls. It's why he and a few others go to the foreigners' temple in the city. But he also knows that he is not as much changed as some. The old brewer could not tolerate the color blue, save for the sky, because that was the color of the bottles she sold the occupying soldiers. The blacksmith built a hidden forge in the woods in case by some unhappy fate her home should be taken.

Alsah, for his part, goes to the bees.

He doesn't have beescraft. His wife did, a very little, and it shone out stronger in their younger boy. Bindun's small magic lies somewhere between beescraft and gardening. Alsah cannot reach blithely into a hive and pull out a dripping honeycomb. He cannot walk blindfolded through the forest to meet a swarm in need of a home. He studies, he guesses, he hopes, and he knows that if he approaches a hive with anything less than a calm heart, it is possible that they will rise up and leave him a swollen-tongued corpse.

He goes to the foreigners' temple when he has killed someone. He goes to the bees for everything else.

When he has checked the hives and convinced himself that he is once again steady, he returns to the house. The boys hang on to the porch like it's the rail of a ship and the yard an angry, serpentine sea.

"You all right?" he calls, and the youngest gives him a wide grin. After a moment, so does Bindun.

The past year hasn't been prosperous for Alsah. Like many, he is supported in part by those who knew him during the war. Like many, he supports others in turn.

It's past time he visited the mad hermits, two women and a man who found a ruined house and dug in like it was a fortress. He loads up a handcart with food from the memorial and walks. The boys follow, wary, like pariah dogs.

"They aren't dangerous. Remember that," he says after a little while, not caring if they're listening because he knows they are. "They don't like new people, but they won't hurt you unless you go into the house. Stay in sight, though, and stick to the path from here." While none of the booby traps are strictly lethal, he's never sure if that's intentional or not, and the boys aren't built like he is.

He calls out a greeting when they enter the yard, and no one answers. His war-trained ears pick up the sound of guns, though, and he carefully doesn't look at the windows or the barn. "I've brought you some leftovers from the memorial. Not much, but even we can't eat all of it."

The boys might not have heard the cricket-clicks; they help him unload and seem just as casual as he is. It took him a long time to learn this false calm.

Almost everything goes on a sturdy worktable in the yard, and Alsah puts a basket down the well to cool. "I'd like you to meet my boys if you've a moment," he says finally, and the door to the house opens.

It's the scarred woman, the one who talks. "I'm Senaille," she says, and bows to the four of them though her face is pointed stubbornly away. "Come, sit on the porch."

"You remember my Bindun," Alsah says, and the boy's head bobs. The other two lean warily toward him.

The woman calling herself Senaille today shrugs herself down the steps and cocks her head. "Here they come." The other two, the man and the silent woman, creep out from the house and the barn. "Lesun. Alessann."

The visit is short and surprisingly refreshing. Alsah knows how to talk to the three war-broken hermits, how to shift from present to past without losing track of who's dead and who's inexplicably alive. He counts himself in the latter category.

When they leave, this time pushing a handcart of early vegetables and blankets, Bindun is quieter than usual. "Why'd they use false names?"

Alsah stops and looks at him before remembering that the boy's only visited the hermits once or twice. "They're not false names. They just aren't theirs. They hardly ever give the same name twice." He walks on, considering how to say the truth without breaking it. "Senaille was one of the road guard. Vicious. I never liked going out with her because she took prisoners, but didn't keep them. She went down to a pair of cavalry with a chain between. I'm not sure about Lesun, never heard of him. Alessann was the hearth mother."

He keeps going, but stops when none of his sons follow.

"Why do they want to be them?" the older boy asks, and his voice is confused, accusing.

Alsah shakes his head. "It was the war. They did things they want to forget. The dead are all they can keep." He picks up the cart and walks on, then stops. "They don't hurt anyone who knows the rules, they make good blankets, they're just more broken than the rest of us."

It was after a visit to the mad hermits that he destroyed the storeroom. The man had called himself Bindun.

After a while, he says, quietly this time, "When they came, the one who called herself Alessann was the only one who could be touched without striking. Your mother was the first to sit with them for an entire afternoon, and she came back hoarse from talking all that time. We make sure they have enough to eat, and they make things. Blankets, hats, take-in work."

"How long has it been?" the little one asks.

"Since they arrived? That was a year, year and a half after. So maybe fourteen years. No, thirteen, because your mother took you to see them after you were born, and that was the first time the man walked up on the porch that any of us knew of, and that was more than a year after they'd arrived. We all made sure the barn was sound before that winter."

"It takes a long time, doesn't it?" the oldest says, his voice small and bleak.

Alsah considers. "It can. It depends what you're walking back from, and who's walking with you."

When the nightmare comes, Alsah is halfway to the door without thought. His son is screaming. He doesn't know which one, but the sound is high and hopeless and he will do anything, he will break necks or hives, he will light his stubbled hair on fire, to make it better.

The door is locked against him.

The bolt is low, a comfortable height for a boy. Alsah can't get enough force with his shoulder. He kicks it in instead.

One of the boys, he can't see, slams into him. Something sharp bites into his arm. It's all he can do to keep from reaching down to screaming shoulders--foreign gods forgive him, no--

Then he's down and it's Bindun sitting on him. Bindun with the weapon. Bindun panting and scared. The two new boys watch, as if it's a test, as if... he didn't fail, did he? No, this son is still alive.

He thinks of bees and asks, "Are you all right? I heard the screaming."

Bindun leans off him. "It was Twi--" the little one begins, but the others shake their heads and he swallows back the words. "I think we're fine."

Alsah waits for everyone to nod, then pushes himself sitting. His arm is bleeding, he notices, but not as badly as if Bindun had a real knife. The boy's clutching a screw stolen from the blacksmith. "I'll put tea on. Have something to eat."

But the youngest boy shakes his head and Bindun says, flatly, "No, we'll be all right."

There is no space in this room for a father. Alsah closes the door behind him, as much as he can with the frame splintered at the bolt.

It is a very long night, alone in the kitchen.

There have been many very long nights this year.

Alsah drinks whiskey the old brewer made in the last year of her life. He considered watering it down with tea, but he's not sure he wants to be wakeful. Besides, there are fewer lies if he drinks the whiskey straight.

Before his third, he stands and walks quietly to the bedroom door. He nudges it open and looks in. All three boys are on one bed, pillows thrown on the floor to make room. The oldest's eyes are open and cold, fixed on the door. Alsah meets them and nods.

Maybe he can't be a father to them. Maybe he'll never be able to do anything for them at all.

But they are his sons.

Part of him isn't surprised when the door opens and the oldest boy comes out, just as quietly.

"Tea?" he asks, his voice a rumble. The boy shakes his head, and Alsah passes over his finger-full mug. "Sit. Please."

The boy perches a little way from the table, like a bird uncertain of its branch. His body eventually relaxes and his feet touch the legs of the chair.

"I'm Alsah." He waves off the boy's glance. "No, no, I know names mean things. It's why I haven't asked yours. You had little enough, I think. But I'm Alsah. I keep bees. I sell honey and candles and mead, sometimes.

"During the war--you know about that? It's done with, over and done, you don't have to worry about foreigners coming in. I mean, you're a foreigner, but--"

"Stop," the boy says. "I'm Twigun."

Twigun. A foreign name, but close enough. Alsah looks at the candles instead of the boy, Twigun, for a moment.

"I killed my first man when I was about your size. Probably younger. I've always been big." Alsah doesn't know where the words are coming from; maybe the part of him that lies awake in the night and knows what happens in the dark holds of ships, the part of him that the bees drive away. "I was guarding a cache of pistols and coin stolen from the fort guards. They left just a few of us because we were hidden and they needed the soldiers." He takes a drink from the bottle. "I don't know if they were looking for us. They saw, and then one grabbed for me, and there was some punching and some brawling and then I got up and he didn't. I still don't know exactly what happened. But any time I got close in with a foreigner, my hands ended up on his head or neck and that was it."

"Bindun kept saying that. 'My papa's gonna break your neck!' was a joke," Twigun says. He's taken only a sip of the whiskey.

Alsah shrugs. "And then you get here, and here's Papa, and," he spreads his hands, helpless. "I'm sorry."

"How many people have you killed?" the boy asks. His eyes gleam in the candlelight.

How many? The first one. The one he didn't. The rest are less important.

"More than a dozen. I can remember that many. But it doesn't mean I'm, I'm a hero or something. Not from the war. Everyone has blood on their back teeth. The woman who made this we're drinking used to sell it to the fort soldiers and every fifth batch was wolfsbane. I never had to try. I mostly watched the horses."

The boy snorts. "Yeah, you watched the horses. You're big as one, sure."

It's an old joke and it heartens Alsah to hear it. "Worst night of my life in the war, the horses and I were captured. Just one soldier, but it only takes one if he has a gun and you're the kind of target I am. He ties me to a tree and says he's going to wait for the rest to get there, then kill them. Or something, I don't know, I was trying not to piss myself. But after a while, I got hold of my balls and he was still gloating, so I spat at him."

"Then he made you dig a hole, so you had a shovel?"

It takes Alsah a moment to figure out what Twigun means. "No, nothing like that. I spat at him and he picked up his gun--" he stands to demonstrate, "and he's going to break my teeth, except he has his back to the horses and one of them's twitchy about sticks. Kicked him in the head, so the rest of the guards found me tied to a tree with a neck-broke man at my feet."

"Serves him right!" Twigun laughs, and Alsah is glad the boy can make such a joyful sound. "Did you tell them it was the horse?"

"I gave that horse every carrot I had. And I had a lot." It feels good to laugh. It feels good not to be alone any more, even if it's this war-blooded part of him in the kitchen with Twigun.

The boy chokes on a swallow of whiskey and laughs harder. "So how'd you end up out here?" he asks when he has his breath back.

Alsah shrugs. "I grew up a ways from the border. I met a pretty girl who smuggled all sorts of things in pots of bees. When I needed a place to stay, after," he doesn't say after what, but Twigun will probably understand, "I came here and learned what I could. It's enough."

"But they still came."

He nods. "That's not the same war."

They're both silent a moment, then Alsah stands and wobbles a little. The boy tries to sneer at him, but it turns into a grin. "You been drinking a lot?"

"Never could hold it. Made it easy, back in the killing days. Before I found the temple."

"I don't know why you go."

It's hard to explain. He fought because he had to, because here was the Queen and here was the Realm and it was unthinkable that he stand by and watch while the foreigners gutted them. But, when it came down to him and anyone trying to kill him, anyone close enough to kill him, it ended with his brawler's hands and a body. "It's wrong to kill people, and I do it. I need rules. I need reasons. The temple gave me some, but before that...."

"But it's not your temple."

"Because it's foreign? So are you. So are long guns."

The boy stands and is steady. "You're weird."

"I know." He considers the light outside. "I'd better start breakfast. I'll leave it on the back of the stove for you three."

"You're going?"

"It's the drink, the temple, or the bees, and I can't drink more than this any more."

Twigun steps between him and the stove, upright and firm, and Alsah marvels at him. "Don't. I can get it. Sit down." He swallows. "Why don't you talk about the war?"

"It's over. It's done. It was supposed to be safe now. Besides, you don't know the people."

"You could tell us."

A quick, regrettable shake of his head. "You remind me of one of the women, a little. Fierce. She got taken by the foreigners." He swallows again. "A lot of the stories end like that."

"What was her name?"

Alsah recoils before he can stop himself. He tries not to even think the names of the dead. For years, he's been surrounded by the brewer's son, the old miller, the grey-eyed twins, the needlecraft archer. His wife. His sons.

"Don't say the names of the dead." He could say more, but it's all tangled up in suffering and loss.

Twigun turns to the stove and piles kindling in, more energetic than knowledgeable. "When he died, Na--the other one, Bindun said his name a lot. In his sleep, he'd say it. He still does sometimes."

Alsah closes his restless, burning eyes and wishes the dark part of him couldn't see a boy in the dark, pleading for his brother to come back, just come back. "It happened sometimes, during the war, that way. I knew a few who died with names on their lips."

"You ever?"

"Never kept anyone under my tongue that way. By the time I did, I knew how to keep living. And that's all it is. You find something that keeps you walking away from the bodies, then something that keeps you walking toward something better, and then something to keep you walking for the sake of walking." Whiskey, the temple, bees, and his sons.

There's a hiss at the stove. Twigun says, "I don't like being drunk. Or priests."

"Then you find something else. Everyone walks his own path."

"You actually do care, don't you?"

Alsah looks at the boy. "Of course. I'd have taken you in if I didn't, for my son's sake, but that's why I go to the temple. To make it so I can still care. The bees, too."

They are quiet a bit while Twigun discovers that stoves are difficult. Alsah heads to the door and leans against it. "I'm going to walk the hives." He's almost sober now.

The boy looks up. "Can I come?" When Alsah leans his head toward the big bedroom and its crooked door, Twigun meets his eyes and says, "They'll be all right."

For the first time, Alsah believes it. He helps his swaying eldest son out the door into the dew-cold morning.

The End

This story was first published on Friday, January 4th, 2013

Become a Member!

We hope you're enjoying Walking Home by Catherine Krahe.

Please support Daily Science Fiction by becoming a member.

Daily Science Fiction is not accepting memberships or donations at this time.

We hope you're enjoying Walking Home by Catherine Krahe.

Please support Daily Science Fiction by becoming a member.

Daily Science Fiction is not accepting memberships or donations at this time.

Rate This Story

Please click to rate this story from 1 (ho-hum) to 7 (excellent!):

Please don't read too much into these ratings. For many reasons, a superior story may not get a superior score.

6.0 Rocket Dragons Average

6.0 Rocket Dragons Average

Join Mailing list

Please join our mailing list and

receive free daily sci-fi (your email address will be kept

100% private):