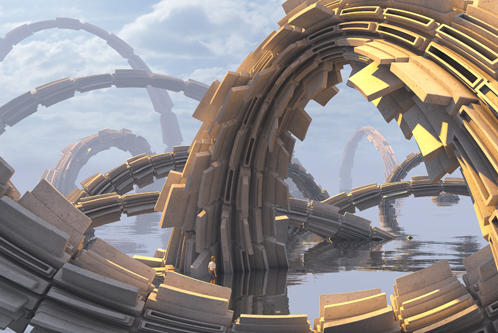

art by Jason Stirret

Foundering Fathers

by Brian K. Lowe

"Soames, you haven't by any chance solved those fourth-dimensional differential equations of yours, have you?"

My valet's face remained impassive, but I had learned by now to read his eyes, which most would term "steady" with perhaps a touch of "stern," and they told me a sad tale of continuing futility.

"Not at this juncture, sir."

"And when, pray tell, might this juncture be located?" Tasting the bitter fruit of experience had taught me that upon our present course, "when" was far more critical than "where." The moment when we returned to the 26th century, I was going to seize one Cyril Bassington-Santiago by the scruff of the neck, and, public school chum or not, pitch him bodily into this infernal used time machine of his and set it on a one-way course to the late Pleistocene. Which, knowing the fickle nature of the mechanism, it would never see.

"According to the chronograph, sir--" Soames made a show of consulting the device. I took this as an uncharacteristic sign of his unease. Soames does not typically make a show of anything he does. "We have emerged in the latter half of the 18th century. I shall know more precisely presently, sir."

I despaired that his use of the word "presently" was a subtle attempt at humor, since for all of Soames's sterling qualities, jollity is absent from their midst. It would be funny, in a gallows sense, since our present was also our past--although to be scrupulously correct, our future was also our past, right up until our present.

"I was thinking rather of the time of day, Soames. I find this undisciplined ratcheting back and forth in time parches the old Webster throat." In truth, though, I feared even Soames's ability to find the makings of a decent scotch and soda prior to 1900.

"Perhaps you should take the opportunity for a small perambulation, sir. Exercise does stimulate the brain."

I thought it would be more productive for him to indulge in some mind-stimulating exercise, while I remained behind in the relative comfort of the chronosphere nursing a soothing beverage. Nevertheless, if my sacrifice could in any way grease the gears of Soames's marvelous thought processes, I was prepared to perform my duty for the greater good.

I let myself out. We were ensconced in a shady lane off of a dirt road. The sun was high, the sky was clear. Spying the outskirts of a town, I strode forth to see the sights.

It took some little time to reach the city center. The streets were crowded; women carried shopping baskets on their arms while dark-skinned servants in colorful scarves held parasols over their heads. Men in long coats and powdered wigs looked as uncomfortable as they did fashionable. My chameleon suit not only mimicked local styles, it protected me from temperature and humidity. It did nothing, however, to protect my sense of smell, which was assaulted on every side. How fortunate that Soames had dispatched me to be my own Mercury on this errand , for amidst such a fragrance of humanity I doubt he would have been able to do less than proclaim the establishment of a public bath, directly here in the street. Such a declamation would doubtless constitute what my nanny would have protested as a Really Bad Idea. Like the crowd, then, it seemed that the time to explore one of the nearby business establishments was ripe.

No sooner did I direct my sight down the street than I espied a sign with a foaming tankard, and there I set my steps.

There were only two patrons in the taproom, conversing quietly. I sat at a rough table and gestured to the nearest servant.

"A glass of your finest ale, my lady."

The Webster men run more toward the genteel and cultivated than the classically handsome, but we have always made up for that with our scandalously fulsome bank accounts. I placed a local coin, supplied by Soames via the ship's computers, on the table.

"And that's yours if I can count on your individual attention."

Her eyes widened as she saw the coin. "You can 'ave as much of my ale as you like, sir," she said loudly, "but we runs a respectable establishment 'ere!" She snapped up the coin and dropped it into her capacious bosom, dropping her voice to a stage whisper. "Me name's Annie."

After a word with the barkeep, she headed for the stairs. I looked at her, then the barkeep, and finally at my empty table.

"Well, sir, you paid for it. Aren't you going to use it?"

One of the pair had turned to examine me. His friend wore an amused expression.

When I frowned, the speaker pointed toward the upstairs where my waitress had disappeared.

"Is that the private salon?" I asked.

He laughed. "You could say that, sir. It's very private."

Now, no one has ever accused the Websters of being megalocephalic (for which I had Soames), but neither are we bringing up the rear of the mob of human evolution. A light burst in my head.

"Oh, heavens. I just wanted a beer. It's so hot."

"Then you have overpaid handsomely. But Mr. Dawes and I would be honored to help consume your credit." He gestured at the barkeep. "Paul Revere, sir, at your service. And my colleague is Mr. William Dawes."

I moved to their table, shaking hands vigorously. Hardly in town and already making friends!

"Barclay Webster. So honored to make your acquaintance."

Three tankards arrived. Mr. Revere made short work of his and ordered three more. When I offered to stake my new friends another round, he assured me that I had already done so. So I toasted their health, and they mine, and then the health of their friend George, and then a different George, and all the while I blessed the 26th century medicines that would keep my blood alcohol levels to no more than a pleasantly fuzzy level…

"To Thomash Paine!" Dawes roared, lifting his glass.

"To Thomash Paine!" we echoed. And we drank.

"Barclay," Revere said, "I want to let you in on a little shecret. Can you keep a shecret?"

I nodded, slowly. "No Webshter hash ever betrayed a shecret."

Revere nodded, too, and I thought his head would fall right off. "Good. Because young William and I and some comrades are working on a bit of mischief that King Georgie would not appresh--appress--like too much. A group of us thinks the colonies should shecede and break away from Great Britain. Whaddaya ya think?"

"Are you talking about a rebellion? People could get hurt!"

Dawes hiccupped. "Good heavens, Paul! He's right! Did we even think about that?"

Revere snored.

"Oh, he's in for the night, then," Dawes declared--and his own head promptly dropped to the table--but a hand from above caught him, lowering his face gently to the wood.

"Soames!"

"Good evening, sir. Will you be returning for supper, or dining out?"

"To be honest, Soames, my friends and I had not even contemplated supper. What time is it?"

"It is well dusk, sir, and if it is not too much of an imposition, I was rather hoping you might be dining out tonight."

I frowned, making the world fold in odd corners until I stopped. This ancient brew was quite heady.

"Really, Soames? Is there some reason you wouldn't want me coming home? Have you a lady friend?"

He nearly blinked. "Oh no, sir. I was researching this time period--" I stole a look at my two companions, but they were dead to the world--"and it appears we have arrived at a very propitious moment. This is April 18, 1775. On this very night Paul Revere and his comrade William Dawes will undertake to warn their fellows of the encroachment of British troops, an event chronicled in a famous poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, long a particular favorite of mine. The opportunity to see the ride itself would be of great interest."

All of the alcohol in my head immediately fled south, leaving me sober as a priest on Sunday.

"Paul--Revere, you say?"

He did not register my apprehension. "Yes, sir. Not only is it the inspiration for a very fine poem, but it is a pivotal moment in 18th century history. Fascinating on many levels, sir."

"I say, Soames, allow me to introduce you to my two friends." I indicated the duo snoring on the table. "This is Mr. William Dawes and Mr. Paul Revere."